Power People

Sunday 15th May 2016, 12.15pm

Did you know that you are in charge of a power station? It’s true. Every time you flick a light switch, a power station somewhere in the UK will respond and generate that little bit of extra power you need for your light. In this animation we look at how we, the consumer, could help researchers solve the ‘peak demand’ problem.

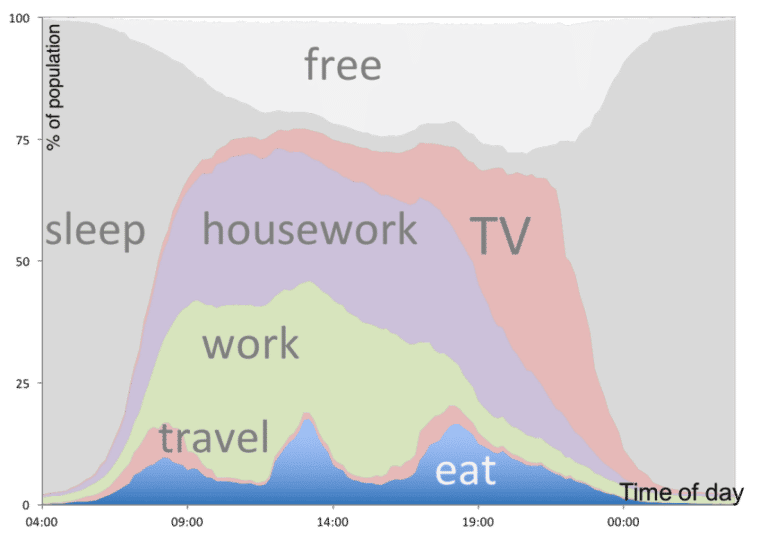

What are you doing right now?

“I want to know what you did on 7 December at 5:30pm. Were you at home? Perhaps having a piece of toast and a cup of tea? Or were you doing housework, vacuum cleaning, putting on a wash?” asks Dr Philipp Grünewald.

This is an important question that Phil is asking to help combat the problem of ‘peak demand’. Put simply, this is when, between us all, we’re using a lot of electricity and putting a strain on the power grid. When power consumption peaks power stations may struggle to cope.

He continues, “Whatever you were doing, you would have used some of the most inefficient, polluting and the most expensive electricity of the year.”

Demand versus supply

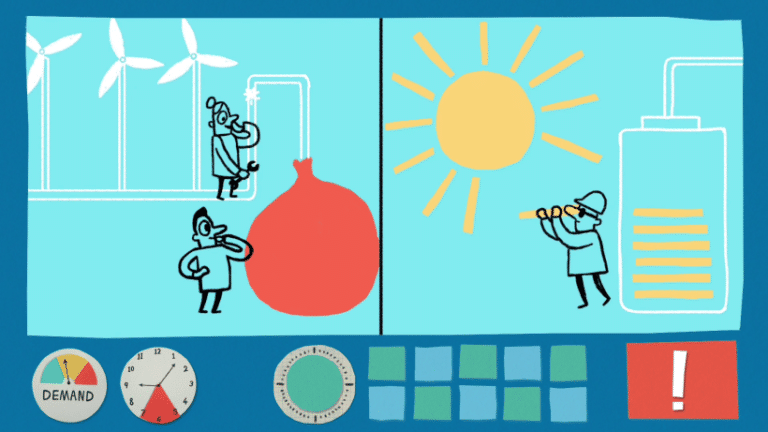

The Electricity Grid uses a mix of different power sources, including fossil fuels, nuclear, hydropower, wind and solar. They all do different jobs. For example, nuclear power stations are ‘on’ most of the time; whereas gas fired power stations keep ramping up and down. Every time you switch on a light, a power station somewhere in the UK will notice that demand has just gone up (by a small amount) and has to immediately respond by burning a little more gas. If they didn’t, very soon the lights would go out – everywhere in the UK!

Every morning they wait for us to start the day and ramp up the power when we need it and they follow all the ups and downs throughout the day. The trouble is, these flexible power stations are also the most dirty and release a lot of greenhouse gases.

In the long run we need to find ways to use more sustainable sources of electricity, such as wind and solar. But the wind doesn’t care much whether we fancy a cup of tea or want to watch TV. If it doesn’t blow we don’t have the electricity.

One of the options is using storage – but it’s a costly option. The same amount of electricity you get from your wall socket for £1 would cost you £10,000 if you bought it in AA batteries – that might make you think twice about running the washing machine.

We already have some storage that was built over 30 years ago. And it is beautifully simple. When we have a lot of electricity we pump water from a lake at the bottom of a hill up onto the top. When we need electricity we let the water rush down through a huge pipe and a generator produces electricity from that flow.

Recent years have also seen great advances in battery technology. Smart phones and the first electric vehicles have done a great deal to bring the costs down. But we need to go a lot further to make this viable at a large scale.

Another option to reduce the strain on the system during peak demand might be to shift some of the energy use away from those critical periods.

If we could identify 1kW (that’s half a dish washer) of flexible electricity use in as little as 1% of UK households, the saving could be greater than £250 million. Not to mention the benefit for the environment.

A knowledge gap

We don’t really know that much about how people are using energy. Studies measuring all of our appliances are so expensive that only a small number of households can participate. Statisticians will tell you that you need thousands of people to take part before the data gives you a true sense of what really goes on. Well, that’s statisticians for you. You, of course, know what you use electricity for.

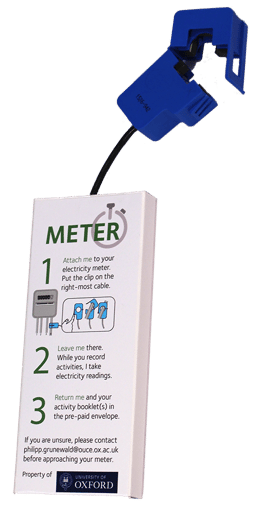

This is why researchers at the University of Oxford are inviting thousands of people from around the UK to take part in an innovative research project. ‘METER’ will help our understanding of what we use electricity for, by simply asking you ‘what you did’, especially at problematic and expensive times of peak energy demand.

An electricity recorder is attached to the electricity meter of a house. This will record how much electricity is being used second by second for just one day.

Everyone in the house is simultaneously asked what they are doing and what appliances or devices they are using. By collecting energy uses across thousands of households a picture starts to emerge of the relationships between ‘what we do’ and ‘how much electricity we use’ for those activities. This is the first phase of the research; getting a ‘baseline’.

A little nudge?

The second phase is the actual experiment. This time it’s not just observation, but people are asked to try and avoid certain things at certain times. Compared to the ‘baseline’ you can see how many people are prepared to run the washing machine an hour later or if anyone can be persuaded not to watch TV for a short while. What might motivate you to make such a change? Could incentives, such as cash, nudge our energy use away from peak times? Or would you prefer to work (or compete) with your neighbours? Or might a little help from ‘smart’ appliances do the trick? For example a smart dish-washer could decide to wait until the sun shines and then use electricity from solar panels.

Individually these may seem like trivial and small changes, but they could avoid generation and network infrastructure costs in the billions of pounds and help us use our natural energy resources more effectively.

The results will not only give a fascinating insight into the diverse uses of electricity in UK households; If effective means to avoid electricity use during critical times can be identified we will produce a cheaper, more reliable and more sustainable energy system.

To take part in this research and for a chance to win a year’s free electricity* visit energy-use.org.

This research is funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC)

What do you think you might be willing to do without for a short period and what would help you be more ‘flexible’? Let us know in the comments below.

*Click here for term and conditions

Contact us to find out more about the following teaching resources:

KS3: Energy Survey

KS4: Supply and Demand

KS5: Incentives