Why do research on research?

Wednesday 22nd Feb 2023, 12.30pm

We’ve talked about a lot of different types of research on this podcast…from investigations into drought, to space exploration, to the future of food. But what about researching ‘research’ itself? That’s right, on this week’s episode of the Big Questions Podcast, we’re going meta! We chat to Dr Patricia Logullo, a meta-researcher from the Nuffield Department for Orthopaedics, Rheumatology and Musculoskeletal Sciences, about why it is so important to examine the practice of research itself, and how scientists such as herself help to ensure research reporting is transparent, complete and reproducible.

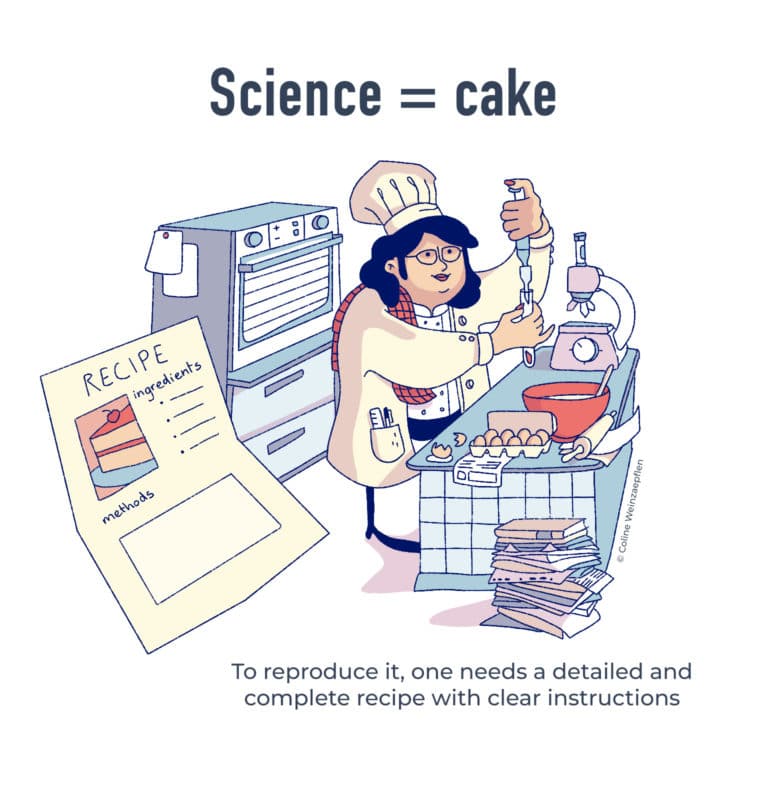

By Oxford Sparks artist-in-residence intern Coline Weinzaepflen.

Emily Elias: We’ve talked about a lot of different kinds of research over the years on this podcast, from fruit flies, to hover-boards, to rice. But what about researching research?

On this episode of the Oxford Sparks Big Questions podcast we are asking, “Why do research on research?”

Hello, I’m Emily Elias, and this is the show where we seek out the brightest minds at the University of Oxford, and we ask them the big questions. And for this one we’ve found a researcher who just can’t stop researching.

Patricia Logullo: Hello, I am Patricia Logullo. I am a meta-researcher, I do research on research. I work in the University of Oxford now, but I come from Brazil, where I worked as a medical writer and as a journalist.

Emily: Okay, so meta-research. I mean, what exactly is it?

Patricia: That’s a difficult word for a simple thing. We research on research. We do investigations of how researchers behave, and what do they do, and how they produce their investigations. How do they produce science, overall?

Emily: So, you’re watching out.

Patricia: Exactly. We’re watching out what our colleagues are doing. Specifically, I research on research in the health area. That means medicine, physical therapy, psychology, anything that relates to human health.

Emily: So, what kinds of issues do you see when you analyse other people’s research?

Patricia: What we know about how to treat disease and how to prevent diseases in the world is based on what is published in the literature. A doctor knows how to treat something because he or she read a paper on it, but in order to use that knowledge, they have to have access to it, and they have to understand exactly how things should be done and how the experience was conducted.

If you give me a recipe to bake a cake and don’t tell me that I need to pre-heat the oven first, I will do things wrong because I’m a terrible cook. Cooking for me, baking, is rocket science. The same thing happens with science.

If we publish reports that are incomplete or vague or misleading, then the next researcher will repeat the same experiment and will do it wrong, and it will take a long time for things to get right again. The body of knowledge that we have is built on not one or two studies, experiments, but on hundreds of them.

One lab conducts one experiment, the other lab has to repeat it to test if the same results happen again. This is called “reproducibility”. For research to be reproducible, the reports must be detailed and complete and clear. We need to ensure in the first place that people who are doing good research, good science, report their papers well for other researchers to understand it, and for the patients, public to understand it as well.

Emily: So, if there are these experiments that are incomplete or vague, or questions about how they’ve been conducted, how do you go about fixing that?

Patricia: We can work on science development, but we can also start by working on size reporting. This is what we do. I’m part of an organisation called The EQUATOR Network. The EQUATOR Network has five centres around the world; one of them is here in Oxford. And EQUATOR stands for Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research.

What we do is that we try to improve the reliability and the value of the health research that is published. We promote these things called “reporting guidelines”. Reporting guidelines are checklists for you to help you write your research report.

So we gather them in a website that anyone can use, and we do meta-research, we do research on research, looking at how people are using reporting guidelines, or not using, or using incompletely, and how they can improve reporting by highlighting, “You know, you forgot to report this, you’ve forgot to report that, this is important”. This way, we are going to improve the transparency of the health research as a whole.

Emily: Why do think these problems keep coming up when you are looking at researching research?

Patricia: Well, sometimes it’s just human error. Lack of training, lack of awareness of the problems. So sometimes it’s just simple, honest error. But sometimes it is fraud, it is fabrication, it is people having to publish a lot of papers in their lives because they are pressed to do that. And, because they have want to publish a lot of papers, they don’t take care of their methodology and they fabricate things.

So, we have to keep an eye of how the literature is going and what people are doing so that we can detect these cases. But not only the cases of misconduct, but also the cases of honest errors, because we can prevent both.

Emily: And these cases of misconduct, is that common or is that fairly rare, that you’re seeing?

Patricia: No. Unfortunately, it is common. And when they are detected, they lead to what we call “paper retraction”. So, the paper, the report that is published in a medical journal, for example, needs to be removed from, the literature removed from the online archives.

Which is terrible, because people are not always aware that a paper has been withdrawn, has been retracted, and they keep citing them as good research. It can do a lot of damage. It can effects patients, participants and the publics’ lives, and the way we treat people for disease.

Emily: How then do you go about fixing all this?

Patricia: So, we can develop reporting guidelines, for example. Reporting guidelines are checklists, or structured guidance, for how researchers should report their experiments and their studies. So, if they use those checklists when they are writing their research, then the risk of them forgetting to report something important becomes much less.

Emily: And what’s it been like working with other members of the scientific community? Does anybody take offense to you guys knocking on their door and going, “Hey, hey, hey, can we make sure that your research is being reported according to our checklist?”

Patricia: Yes, sometimes people come to us to ask for us to evaluate their research, to see if they are complete.

We are now conducting a trial on this. We are, for example, evaluating reports of several kinds of research from people using and not using the reporting guidelines. So we have to take their papers and evaluate if all of the items in the checklist were reported. So we do that all the time.

People do ask for help. They do come to our courses. We have short courses, we have long courses, and we also provide guidance and consultancy to research groups internationally.

Emily: What does the future look like to you? What does improving look like?

Patricia: Okay, the future. I wish that we could involve more people to it. I mean, involving the citizens’ population, people who are not researchers, who are not involved in academia, they should know more about this. They should get an interest on research, because, you know what, research is done using the money that they give to funders, to charities, to the government via tax paying, so they should get interested in it and engage with research on research. I would very much like to see that, and I think it’s already starting.

Another thing that the future should bring is more training for researchers to perform, to develop their research, and also to report them. They are very poorly trained during their graduations and post-graduation courses, so there should be more about that.

And also we should make our reporting guidelines stronger by implementing them, helping people to get their hands on them and use them, and testing their use also.

Emily: So, checklists for everyone?

Patricia: Checklists for everyone, and people should understand that checklists are there to help them, not to restrain them. To help them write. It really makes it much easier to write when you have a checklist on your hand.

Emily: This podcast was brought to you by Oxford Sparks from the University of Oxford.

With music by John Lyons, and a special thanks to Patricia Logullo.

Tell us what you think about this podcast, you can find on us on social media. We are @OxfordSparks. And we’ve got a website, oxfordsparks.ox.ac.uk.

I’ve said it once, I’ve said it twice, I’ve said it a thousand times. I’m Emily Elias, bye for now.

Transcribed by UK Transcription.