Brain development in teenagers

Friday 10th Mar 2017, 11.48am

As you journey from childhood into your teen years and then into adulthood, your brain is changing in ways that might explain why the teen years can be a bit of a roller coaster. In this animation we take a look at what’s happening in teenagers’ heads and how researchers at the University of Oxford are trying to understand this important developmental period better.

Our brain is the control centre of our body and responsible for our thoughts, actions and overall function of the body. But it doesn’t stay the same as we grow up. It’s continually changing and developing. One of the most fascinating transitions for the brain is between childhood and adulthood: your teenage years.

At this point in our lives there are three important things happening in our heads:

1) Slow development over long periods of time of parts of the brain that are involved in controlling attention, resisting distraction and impulses, as well as decision making;

2) Faster development and increased functional activity in areas of the brain that are involved in emotion, appetite and mood; your ‘gut reactions’;

3) the connections (“cross-talk”) between these parts of the brain becomes increasingly efficient.

A rollercoaster ride

In terms of brain development, adolescence represents a “perfect storm”: on the one hand a great interest in socially rewarding stimuli and increased interaction with peers but slowly developing control of emotions, rational and affective judgements on the other hand. The interplay between these functions and, in brain terms, their changing “cross-talk”, may explain why adolescence is characterised by a high incidence of risk-taking behaviour and high risk of developing social anxiety. It might also explain the positives: exploration, enthusiasm for new experiences. We also know that teenagers’ sleeping patterns change.

Neural Pruning

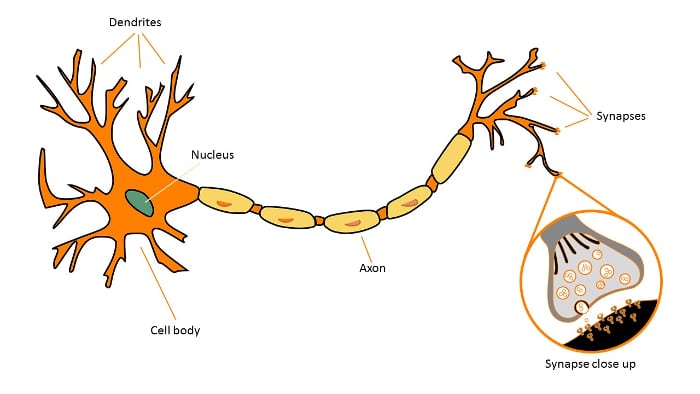

One of the mechanisms behind this ‘mismatch’ might be the process of ‘neural pruning’. Neurones are the ‘wires’ through which your brain’s messages are sent.

Between childhood and adolescence our brains increase in size, but the actual numbers of neurones remain the same. What actually changes is the ‘insulation’ of the nerones, and importantly the numbers of connections, or synapses, between the neurones. About 20 per cent of the body’s energy is channelled to the brain, yet it remains staggeringly efficient, consuming less energy than a filament light bulb.

Throughout our lives, well-used connections become stronger, whilst weaker connections are cleared away. It may be the case that this process is happening at different rates in different areas of the brains during our teen years.

It might sound a little weird to be ‘pruning’ away connections, what if you need them? But it’s exactly this process that leads to our brains becoming highly efficient and able to change as a result of, for example, learning. This might explain why adolescence is also a period of marked flexibility to positive interactions, high interest in learning new activities and engaging in social opportunities.

But don’t worry about needing to grow up too quickly; the process of maturation in the brain isn’t complete until we’re well into our twenties.

Now we’ve got your attention…

What we pay attention to shapes how we act upon and learn from our environment, which might sound like a simple idea, but we still don’t fully understand why we pay attention to some things and not others, and why this is different in different people – or how attentive difficulty impacts on learning over developmental time.

With her research team, collaborators at the Brain and Cognition Lab and the Researching Emotional Disorders and Development group at Oxford and King’s College London, Gaia has been developing neurocognitive tools that investigate the social brain and how its development shapes attention to people in our environment.

They have used a combination of eye-tracking (Doherty et al., 2017, Cognition; Haller et al., under review, Dev Cognitive Neuroscience), functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI, Haller et al., in preparation) and electroencephalography (EEG, Doherty et al., in preparation).

One of their studies has looked at how adolescents interpret social scenes. They found that those who paid more attention to the faces of people in photographs of social scenes were more likely to be socially anxious. But they also found that older teenagers were less likely in general to report negative interpretations.

We know that over adolescence several parts of the brain that are important for social cue interpretation and attention regulation, and their functional connections, are slowly developing.

Whilst uncomfortable, feeling anxious during your teenage years is perfectly normally for most. But the hope is that, in understanding what is behind what we pay attention to in social situations and how we draw interpretations of what is happening during these years, we can gain a better understanding of how emotional difficulties (including social anxiety) develop and can be effectively alleviated.

We still don’t fully understand why we pay attention to some things and not others.

This animation featured as part of the ‘Brain Diaries’ exhibition at the University of Oxford Museum of Natural History (between 10 March 2017 and 1 January 2018). Click here to explore the online version of the exhibition.

Contact us to find out about the following teaching resources:

KS4: Alcohol and the adolescent brain

KS4: The Brain Game

KS5: Studying social anxiety

At-home activity: The Brain Game