What’s an arboretum anyway?

Wednesday 26th May 2021, 1.14pm

An arboretum could be described as a “living library”. A beautifully curated collection of woody plants (trees and shrubs) from across the globe, each one carefully labelled and managed. In this episode of the Big Questions Podcast we chat to Ben Jones, Arboretum Curator at the University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Harcourt Arboretum, about what makes an arboretum so special.

The Threatened Tree Trail

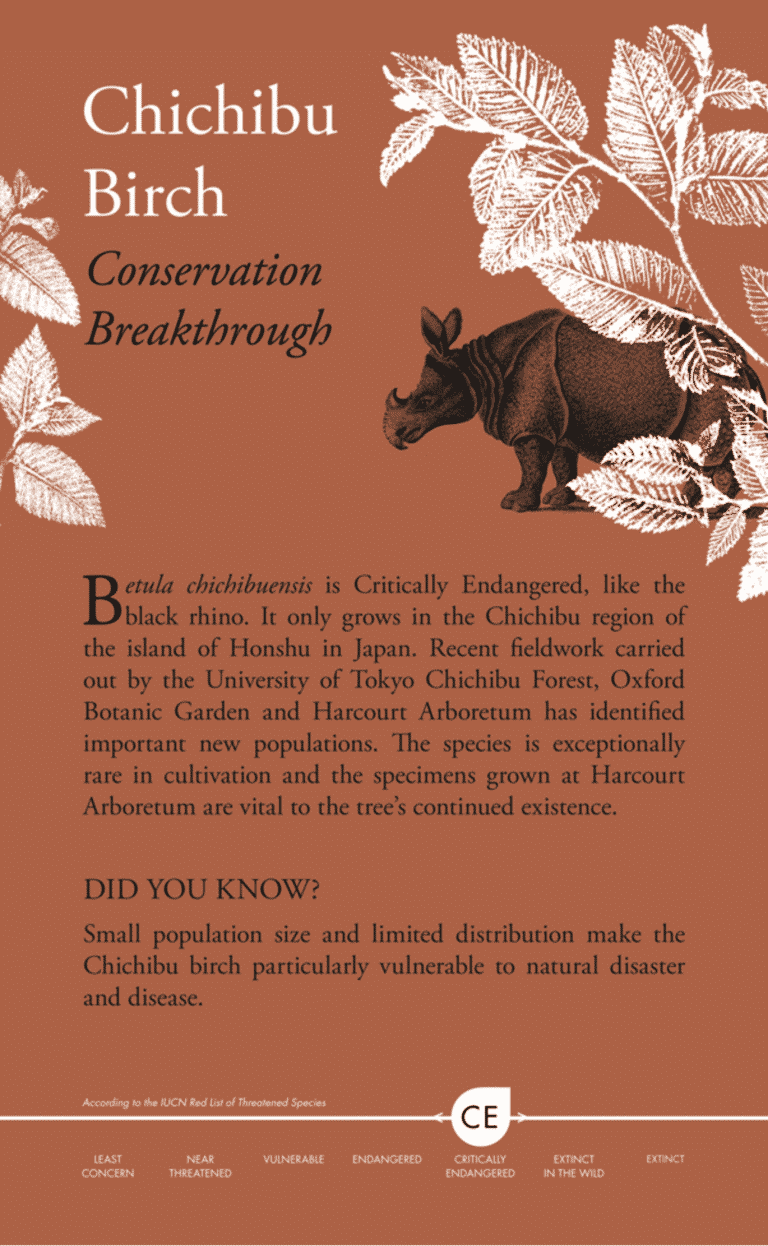

If someone asked you to name an endangered species, what would you say? It’s likely that one or two animal species would spring to mind…the black rhino or the giant panda, for instance. But what about endangered plants? It can be difficult to think about trees and plants in this way, so at the Harcourt Arboretum, Ben has introduced the Threatened Tree Trail. For each threatened tree species, an animal with an equivalent conservation status is given. An example can be seen in the poster below – the Chichibu birch is as endangered as the black rhino!

Find our more about the Chicibu birch here.

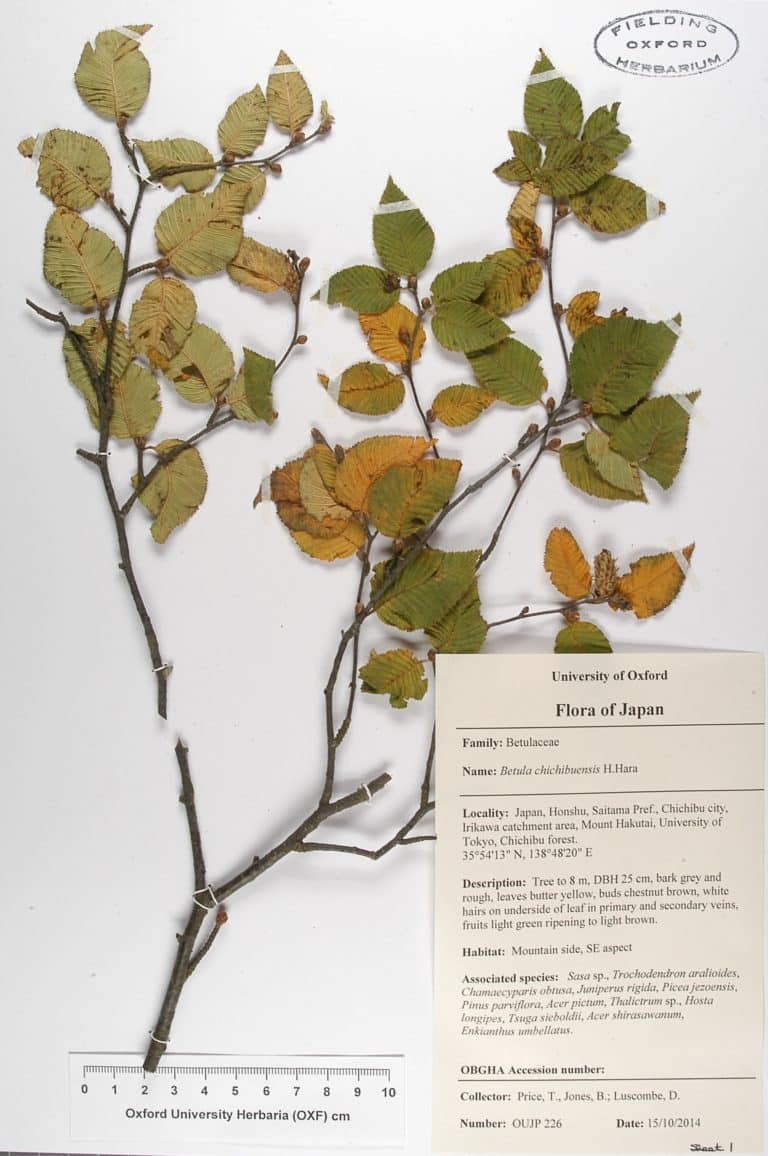

Herbarium sample of the Chichibu birch:

Emily Elias: Trees, they’re pretty great, aren’t they? Over this past year, I’ve definitely had more appreciation for them than I’ve probably had most of my life. Did you know that there is a place in Oxford with a pretty wild collection of trees? On this episode of the Oxford Sparks Big Questions podcast, we are venturing outside and we are asking, “What’s an arboretum, anyway?”

Hello, I’m Emily Elias, and this is the show where we seek out the brightest minds at the University of Oxford and we ask them the big questions. For this one, we’ve not only found a tree expert but some pesky peacocks.

Ben Jones: [Bird squarking.] Yes, that was our peacocks. (Laughter) They have a habit of doing that: coming up behind people and, yes, making their presence known.

Emily: Amazing.

Ben: Yes. My name is Ben Jones, and I’m the Curator of the Arboretum. That’s part of the University of Oxford Botanic Garden and Arboretum. We’re based just outside the city, at Nuneham Courtenay. Essentially, as my role as Curator, I have the responsibility for managing the living collections, the trees and shrubs that form part of the arboretum.

Emily: Okay. First of all, what the heck is an arboretum?

Ben: An arboretum is a collection of woody plants, so trees and shrubs. This arboretum here, the Harcourt Arboretum, the site is 130 acres and comprises of wildflower meadows, of semi-natural woodland and then the historic landscape, which is the more formal part of the arboretum.

The best way I can describe an arboretum is to compare it to, almost, like a living library. So, the trees and shrubs that form part of the arboretum all have a label on and will have their scientific names, their common names, countries where you would find those species normally, but we also have a plant records database.

In that database, linked to each of those individual trees and shrubs, is a wealth of data, which could range from fieldwork notes, so what was grown with those plants when we collected the seed, through to more of a management set of notes around any works that we’ve carried out on those trees,

Emily: Why would you need to keep all of this together in one place?

Ben: I suppose it’s a little bit like medical records: having that data builds a picture for us, but it also forms a really valuable resource in terms of teaching, research, engagement with our visitors.

I think, also, a lot of this information becomes more valuable the longer that time goes on. For example, we record temperature. We have various sensors across the site that’s recording the temperature every 15 minutes. Over 5 years, 10 years, 30 years, that data becomes more and more valuable and can inform a whole range of things, from horticultural management of the site, through to how climate change is affecting plants. Yes, so, kind of, like a librarian, but of trees and shrubs, if that makes sense.

Emily: There are a lot of trees here. You’ve got some towering redwoods that I’m used to seeing back on the West Coast of Canada.

Ben: Not too far from where we’re stood at the moment, we have a Juniperus procera, which is an East African conifer and, in fact, has grown from seed collected on Mount Kilimanjaro.

Emily: You’ve got this whole range of Japanese trees and shrubberies that not only look pretty, but they have these distinct needles and leaves that you just don’t see in the UK.

Ben: Again, this is one of the values of the site, I believe, is that, if I go by the books, you wouldn’t plant it, because Benson down the road is often the coldest spot in the country. In the winter of 2010 into ’11, it went down to minus 21 and yet I’ve got conifers growing here from East Africa, from Brazil, all over the world. For me, that’s really exciting to watch these plants, watch them grow and develop, and see how they respond.

Emily: How did this site get started?

Ben: The Harcourt family built the big house in Nuneham Courtenay in the early 18th century. During that period of time, there was this real fascination with plants that were coming in. It was one way of displaying one’s wealth, so in the early 19th century the Harcourt family started acquiring plants that were coming in from the Pacific Northwest or different parts of the world.

Emily: And it then fell into the university’s hands?

Ben: Yes, so ownership has chopped and changed over the years. During the Second World War, the RAF had the big house and operated out of there, analysing aerial photographs taken over mainland Europe, but ultimately, by the time we hit the late ‘50s, early ‘60s, the botanic garden bought what we now know to be the arboretum.

The reason they did that was because it meant that, as a department, we could broaden the range of plants we could grow. The arboretum, actually, as a site, has quite acidic soil, which is very rare, very unusual for Oxfordshire, and so you can grow rhododendrons, camellias, all manner of things that typically you couldn’t elsewhere in the county.

Emily: You’ve obviously not been here since the 1960s; otherwise, a heck of some plastic surgery that has gone on.

Ben: Yes, aged very well. Yes. (Laughter)

Emily: So, as a curator of this collection, obviously you’re adding to it. How do you even tackle a job like that, to be adding to this incredible space that already has so many trees, and bushes, and plants, and flowers?

Ben: We have these different core themes for our collections, both here and at the garden, which are around taxonomy and evolution, conservation, biodiversity, heritage and landscape. So, within that, I can then apply those themes to the arboretum.

There are many things that I have to consider, from biosecurity and plant health, climate change, the age structure of the collection. Within that, I then build into the collection new trees and shrubs to enhance the arboretum, but in line with that sort of vision and strategy.

Emily: Tucked away from the public, Ben shows me the future additions to the arboretum.

Ben: We’re in the nursery, and the structure that we’re in is called a ‘shade frame’. We receive plants at a point where they just require one more season in this sort of environment, where they’re on an irrigation system. Then, after one growing season in here, they’re then at a stage that they can be planted out in the arboretum.

Emily: It, kind of, looks like a mini-garden centre about the size of a bedroom. There are just rows and rows of little trees and little black pots, but these are not your average trees.

Ben: In and amongst us, just looking at what we’ve got in front of us, we have – well, I only know the scientific name of this. This is Euptelea polyandra, which is an endemic tree from Japan, but we’ve got some other things that people will be, perhaps, more familiar with. We have Pieris japonica. We’ve got some oaks. We’ve got some maples, liquid amber. We’ve got some Sorbus.

Emily: When you’re planning to put something into the arboretum and you’re looking at that vision, obviously you’re not planning for, like, next spring, next summer, “Here are some pretty flowers for people to enjoy.” What kind of scale are you working on?

Ben: Yes, so my vision, my timeline, really, has to be 100, 150 years. When we plant these trees, the hope is that they’re going to be there for 100, 150 years or more. So, that has to be our vision, really, because it’s great that we can visit the arboretum, see these great, big 30/40m-tall trees and enjoy those treescapes. As Curator, I need to ensure that grandchildren, great grandchildren, if not beyond, can have a similar experience in years to come.

So, there is a very fine balance between keeping our visitors safe, which means having to take out some of these big, old trees sometimes, but we have a responsibility to find uses for those trees when they come down. But it also gives us a great opportunity for planting new material that, hopefully, will be here for decades, if not more, to come.

We’ve got material that has grown from seed collected, probably, off six different continents. Our flagship project, if you like, is focused on Japan and so we’ve got plants here that are critically endangered or endangered in the wild, that are now growing successfully here, forming, hopefully, the arboretum of the future.

Emily: Now, when you say, “Critically endangered,” usually that’s something in my mind that goes straight towards animals, like rhinos, and tigers and that sort of thing, but you can have critically endangered trees. How does that work?

Ben: This is a very good point, actually, and something I often talk about, which is that, if we go and ask members of the public to name an animal threatened with extinction, we’re able to do so with relative ease: rhinos, tigers, lions, etc. That’s fairly easy for people to grasp, but, globally, two in five plant species are threatened with extinction. If we asked people to name a plant that is threatened with extinction, I wonder how good a response that we would get.

In order to try and tackle that, I’ve thought long and hard about how we make it feel or sound less abstract, especially with plants. So, I made a list of 20 trees that we have growing at the arboretum here, and some of which don’t exist in the wild anymore. Thinking on this, I realised that, if all of those trees turned into their animal counterpart, we’d have the most amazing zoo.

The International Union for the Conservation of Nature, the IUCN, conduct what’s called ‘Red List assessments’. That’s where experts will assess flora or fauna in terms of their conservation assessment. That’s where you get critically endangered, or endangered, vulnerable, near threatened, etc.

With that list of trees, I then looked up their conservation status and then, using that conservation status, I aligned them with their animal counterpart, if you like. We’ve developed a trail here, the Threatened Tree Trail. So, for example, the giant redwood from California is as threatened as the blue whale. Monkey puzzles that are fairly commonly planted in the UK in gardens, that is as endangered as a rhino, in fact.

So, my hope is, by making that comparison, putting it into that sort of context, that it just becomes a little bit more prominent in people’s mind. Hopefully, whilst they’re here at the arboretum, enjoying the peacocks or the blue bells and so forth, people can – in a fun way, I hope – learn something about the fragility of plants.

Emily: I know you’re a future man. Like, that’s probably somewhere in your job description, is that you think about the future.

Ben: Yes.

Emily: What does this place look like in 150 years?

Ben: Yes, I certainly hope that the arboretum is still here, and with a very strong tree collection, and is still being utilised by the university but also is a place for the public to come, and unwind, and relax, and enjoy and engage with nature. I was going to say, “I’d still like to see peacocks in the arboretum,” but maybe they won’t be here in 150 years. (Laughter)

Emily: This podcast was brought to you by Oxford Sparks from the University of Oxford, with music by John Lyons and a special thanks to Ben Jones and all the folks at the arboretum. If you want to learn more about Ben’s endangered tree list and their animal counterparts, just go to our website: ‘oxfordsparks.ox.ac.uk’. Or, if you just want to check out some pretty pictures of those peacocks, we’ve got those on all of our social media places. Just search ‘@OxfordSparks’. I’m Emily Elias. Bye for now.

Transcribed by UK Transcription.