What is quantum computing?

Wednesday 26th Nov 2025, 12.30pm

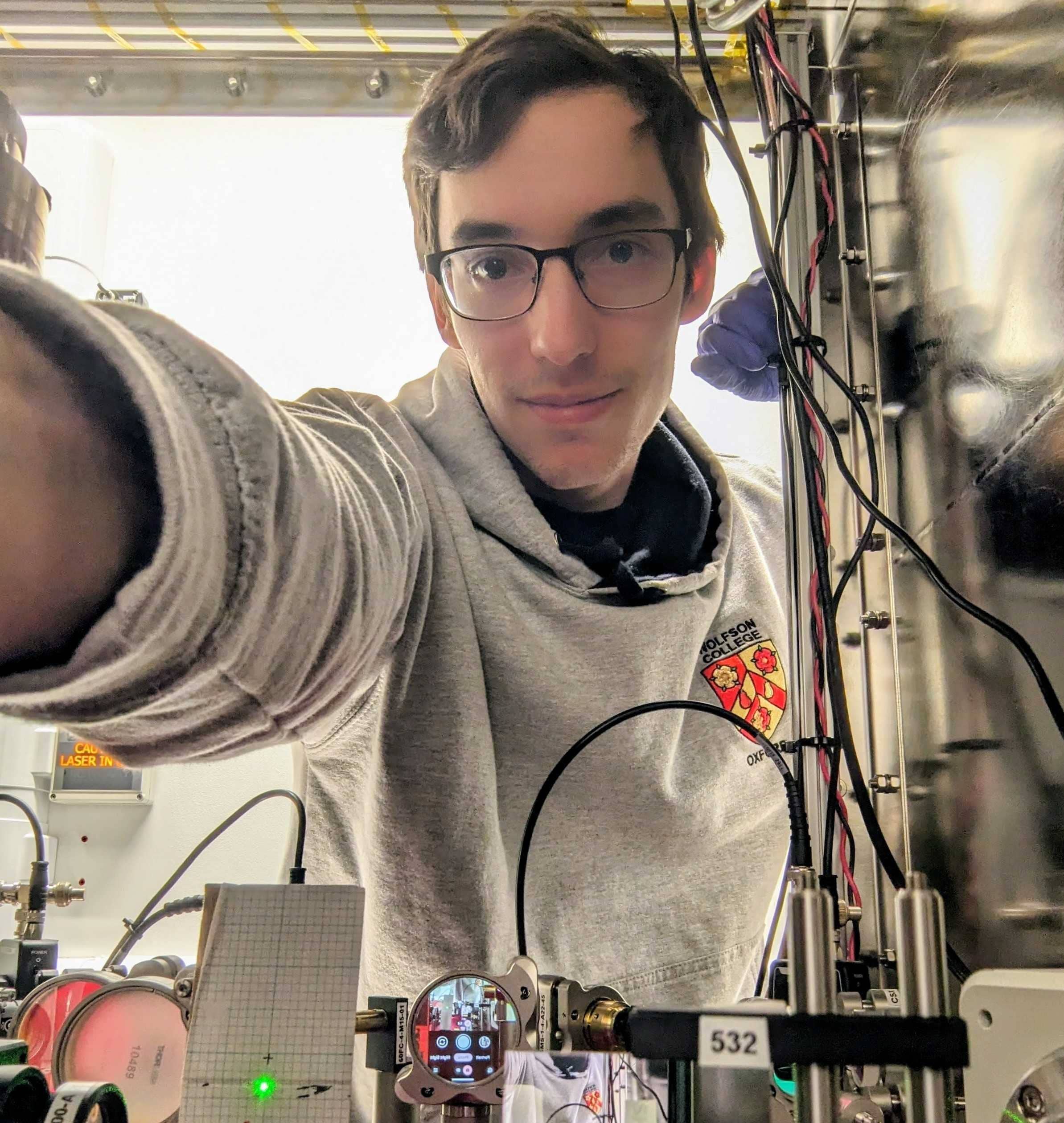

Want to make something feel immediately complicated, inaccessible or downright mysterious? Stick the word ‘quantum’ in front of it. Or, at least, that’s how many of us feel. But don’t worry! Experimental physicist William Cutler from Oxford’s Department of Physics is here to break things down, explaining exactly what a quantum computer is, and sharing the remarkable potential that quantum computing holds for advancing fields ranging from drug-discovery to internet security.

Emily Elias: You know that feeling when you hear a word and you nod along and you pretend that you know what it means, but really, deep down you have no clue. That is me and quantum computing. On this episode of the Oxford Sparks Big Questions podcast, I’m gonna ask some questions that I should probably be embarrassed to ask. But hey, here goes. What is quantum computing?

Hello, I’m Emily Elias, and this is the show where we seek out the brightest minds at the University of Oxford, and we ask them the big questions. And for this one, we have found a researcher who is about to take a quantum leap with me.

William Cutler: My name is William Cutler. I am a second year DPhil student here at University of Oxford, and my research is on trapped ion Quantum computing, which in a nutshell means that we shoot lasers at atoms to make them do math.

Emily: I hear that it is International Year of the quantum. I went to the shop. They didn’t have a card for me to give you, but, um, you know, there we go. I feel like the words you just said sound very scary to me in sequence. From context, I want to say, like, I understand what they are, but maybe we can just, like, really do some handholding to help me understand what quantum computing actually means. So…

William: Sounds good.

Emily: Just to make sure we start on the same page, let’s like back all the way up to like what is computing before we even tack the word quantum in front of it. So what is computing when you talk about computing?

William: Yeah, I think that’s actually a great way to start, because with the right definition of classical computing, which is the computing that your iPhone and laptop and supercomputers use with the right definition of classical computing. Then it’s kind of straightforward to see where the quantum actually comes in. So at its core, a computer is something that is capable of keeping track of information. It can have a variety of states that exist physically on some system, and it has the ability to manipulate those states. And that sounds very abstract. And I, I kind of intend it to be that way because, for example, even if you had just some cards on a table and you were just interested in are your cards face up or face down, you could think of each card, whether it’s face up, maybe that’s a zero face down. Maybe you call that a one, and then having a row of cards is sort of like having a register of bits on a computer, and you, as a human, could run a little program where you follow a very specific sequence of flipping cards and reading whether some cards are flipped or not flipped. And you could be a computer program. So you have some information, you can manipulate the cards and something doing the manipulating you in your hands in a normal computer. Instead of cards, we have semiconductors and transistors, and your zero and one is whether you have some amount of current going through a transistor and a computer, kind of at the lowest level, is responsible for reading instructions on how to manipulate information stored in this current, whether it’s on or off, and can use that to represent and solve mathematical computational problems.

Emily: So deck of cards, whether face up, face down I get it. Okay. And then when you bring sort of like my laptop or my phone into play, those are just making much more complicated. The fake card is up or down very quickly. Uh, so that I’m not having to even think about it, because I don’t.

William: Exactly. Yes. So so the fact that the manipulation of those cards happens through electric currents and electricity can go incredibly fast, and it can scale very well so they can fit so many, you know, electronic cards that I put in, quotes. We can fit so many electronic cards in such a small space as as these chips get bigger and bigger.

Emily: So now if I put the word quantum in front of computing, I’ve got my cards. Do they still exist or do I need something else to visualise this?

William: So you will want something else to visualise it. A quantum state has a few key features that both make them way more interesting, and also actually are what enable quantum computing to be so potentially groundbreaking. So instead of cards in our classical bits, which can either be face up or face down, and you just have those two options, a quantum bit or a qubit instead can take on a continuum of possibilities. And the way I like to visualise this is the same way you would think about a location on the Earth’s surface.

Emily: What do you mean, like in a globe? Or like…

William: Yeah, yeah, on the surface of a sphere. Okay. Um, and on the surface of a sphere, on the surface of Earth, you need a latitude that tells you how far north and south you are, and a longitude which gives you some kind of angle going all the way around the equator or something like that. And on this quantum Earth, if you will, our North Pole, uh, we’ll still call that a zero. Like a zero state. And on the South Pole, we’ll call that a one state. And if your quantum state is at the North Pole, it is a zero. It’s essentially a classical zero. And there’s nothing kind of quantum about that. Same if it’s at the South Pole, it’s a one, and there’s nothing quantum about it. The quantum comes in when you have states that are in between. So for example, on the equator here you’re halfway between zero and one. And that would correspond to a quantum state that if you looked at it, if you measured it half of the time, you would see a zero, and the other half of the time you would see a one. Um, and so what this means is that our quantum states can have a whole range of probabilities of being between zero and one, and they also have the interesting ability to be very different from each other, even at the same level on the equator.

Emily: So if I’m visualising a globe and I have all the little lines of longitude and latitude on it. Each different line, each different coordinate on the globe would translate to something different in terms of like if I was looking at this as a quantum qubit, similar to like if I was trying to find a city on the globe, and I know exactly what those coordinates are on a quantum bit, all those little fake cities or mountains would do different things and act in different ways.

William: Yeah, that’s and that’s the fascinating thing, because every point on the globe is a point that we can observe and we can differentiate from all of the other points. And this is a bit counterintuitive, because on the equator, I’ve just said, every point on the equator has a fifty percent chance of measuring zero and a fifty percent chance of measuring one. I mean, what else can you do? That sounds like they would all be the same. Um, but it turns out that there is another number, uh, that it’s called a phase. But all we need to know is that it’s just another number that describes an additional relationship between the zero and the one, and that by doing the right kind of experiments, we can actually measure that phase and tell that a point on one side, one on the equator, on one side of the Earth, is completely different from a point on the equator on the other side of the Earth.

Emily: And so, like with the cards, where I only had two options, it was face up, face down on the globe, because I have all of these different sort of longitude and latitude points that I can go around. It gives you more possibilities for computing equations. Is that right?

William: Definitely. It’s important to realise that just having the globe and having all these continuum of possibilities, that in and of itself isn’t enough to make quantum computing, you know, amazing and spectacular, but it is a critical part of that equation.

Emily: Don’t worry, I won’t call the math police.

William: That’s a good thing, because I would be long in jail as an experimentalist if I were chased after by the math police.

Emily: So what does a quantum computer look like? Is it like my laptop where it’s got a bunch of chips and wires and things that are, like talking to each other on the inside that I don’t see.

William: And it’s definitely quite different from what’s going on in our laptop, where you can imagine a green rectangle that’s your that’s your motherboard, and it’s got all sorts of little electronic components that are small, but, you know, ultimately not crazy complex. And in a quantum computer similar to the classical computer, where you need something that has states that you can manipulate and something to manipulate those states, that’s what we’re looking for. And so there are many different forms of quantum computers, because there are many different systems that can behave quantum mechanically and have states that are very well defined and very easily controlled.

Emily: So like quantum computer is a very big umbrella term for a lot of

William: it’s a big umbrella,

Emily: like different things that could be doing the calculations or the activities within the

William: definitely, definitely. And there could very well be more platforms for quantum computing than that are yet to be discovered. So in our lab, what this looks like is quite an obscure looking device that just it just looks like a big metal box on a single large table, maybe the size of your dining room table. But inside are all these interesting optical components and very precisely measured out metal electrodes. You have a small metal set of electrodes in the middle that kind of controls the world, that are our atoms our ions will live in. And this is housed in a bit of a larger vacuum chamber, and on the rest of this table are a whole bunch of lenses and mirrors and other optical components that guide and control the lasers that we want to send into the atoms to get it at the right power and frequency and all the other properties we want. We also have a camera that we use to actually look at the ions, which I think is really, really awesome. And it all is actually housed in a metal box that protects it from stray magnetic fields.

Emily: And so let’s get into like the actual examples of like, what are the things that a quantum computer could do?

William: Yeah. One would be the interaction of a potential drug molecule with receptors on a cell. That is chemistry at the end of the day, and chemistry at the end of the day is quantum mechanics. But that Interaction. If that molecule has hundreds of atoms and that cell receptor also has hundreds of atoms, there’s no chance of being able to simulate that completely on a classical device by being able to simulate it on a quantum computer. You could imagine a researcher who’s trying to design a drug to address a particular issue. They could come up with hundreds of thousands or millions of different drug candidates, and then test them all on a quantum computer much, much faster than they would ever be able to test them in an actual biological lab, because the turnaround time for the computation would be much faster than real life. You’re simulating the problem directly.

Emily: Well, that sounds pretty good. Is there anything else you can use it for?

William: So there are loads of other quantum systems worth simulating. But what also fascinates me is that quantum computing has a very significant impact on the future of internet security, because with a sufficiently large quantum computer, you could run Shor’s algorithm, which can efficiently factorise integers. And as a result, could be used eventually to break public key cryptography and encryption. So this is a bit of a it’s a bit of an important application, although one that is more, more one to be wary of and to prepare for,

Emily: because it can act as like a master unlocking key or a master lock and key to keep your information data super, super, super secure or oopsie doopsie, I’ve just got a key to the internet and I can open up every secret thing that exists out there.

William: Yeah, yeah. This is why a lot of governments and security firms are very interested in quantum computing, and also interested in developing algorithms that are immune to quantum cryptography, speed ups. And thankfully, those already exist. And a lot of things on the internet are being converted over to what’s known as quantum proof or post-quantum cryptography. So this is an ongoing process that is really interesting because if you’re not in the quantum computing world, you might not have been aware that a lot of the internet was, number one, prone to being decrypted, but then is also being switched over. And new things that are being encrypted are encrypted in a much safer way.

Emily: Should I be afraid of quantum computing or should I be celebrating quantum computing?

William: I definitely think we should be celebrating it, because the benefits of being able to simulate other quantum systems, and the possibilities for all sorts of other algorithmic speedups that are yet to be discovered, is absolutely game changing. I mean, this could dramatically increase the pace of medical research of material science research of exploring profound mysteries in physics like high temperature superconductors and all sorts of exotic materials that we only can understand quantum mechanically, but we aren’t able to simulate and fully explain why they behave the way they do. And a quantum computer could be a massive help for that.

Emily: This podcast was brought to you by Oxford Sparks from the University of Oxford, with music by John Lyons, and a special thanks to William Cutler.

Tell us what you think about this podcast. We’re on the internet at Oxford Sparks or go to our website, oxfordsparks.ox.ac.uk.

I’m Emily Elias. Bye for now.