Cultural Heritage on the Frontline: the destruction of peoples and identities in war

Monday 3rd Oct 2022, 3.57pm

The Russian invasion has precipitated humanitarian challenges not seen in Europe since the Second World War. It has also seen the deliberate damage of hundreds of places of worship, museums, historic buildings, and memorials. Cultural heritage has also been destroyed and weaponised at scale in recent conflicts in Ethiopia, Mali, Myanmar, Nagorno-Karabakh, Somali, and Syria.

The systematic destruction of heritage often forms part of strategic acts of ‘culturecide’. The obliteration and theft of cultural heritage from Jewish and Roma peoples throughout Nazi-occupied Europe during the Second World War was such an offensive, compounding the drive to dehumanise and delegitimise entire ethnicities. More recently, a campaign of malicious cultural ‘unfixing’, accompanied by extreme physical and sexual violence, was prosecuted by Daesh (Islamic State) against the Yazidi and other communities in Iraq and Syria. Women, specifically, were brutalised and left bereft of gender-specific cultural norms.

The systematic destruction of heritage often forms part of strategic acts of ‘culturecide’. The obliteration and theft of cultural heritage from Jewish and Roma peoples throughout Nazi-occupied Europe during the Second World War was such an offensive,

There are many reasons why conflict actors – from the forces of large states to lone wolf terrorists – train their sights on cultural heritage. Attacks on both tangible (buildings, monuments, and artefacts) and intangible (practices, customs, and knowledges) heritage are not only forms of propaganda by deed, but serve to deny people their very identities – their sense of self.

This loss is particularly egregious as cultural heritage is central to a person’s sense of belonging and attachment to place. It anchors, orientates, and locates a person, a people, in time and space. In short, this destruction disrupts and dislocates, often leaving victims psychologically adrift and emotionally hopeless.

Cultural heritage is central to a person’s sense of belonging and attachment to place….destruction disrupts and dislocates, often leaving victims psychologically adrift and emotionally hopeless

International Humanitarian Law, including The Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict (1954), to which 133 state parties – including Russia – are currently signatories, require states to ensure heritage is not damaged or misappropriated in war. The exception to such protection is military necessity. Thus, forces are permitted to damage heritage, if an adversary is utilising it to present a threat. It is legitimate, for example, for a military force to use proportionate means to neutralise a sniper in a church spire.

Despite these legal protections, however, cultural heritage remains a strategic target in war and conflict. There are, in fact, many reasons why these attacks occur. They are often intended to impact self-identity and denude the will to fight (for instance in ‘The Blitz’, 1940-1), or they can be the means to punish an adversary (for instance, the ‘carpet bombing’ of Hamburg, 1943). Other motivators include: iconoclasm, the removal of symbols of legitimacy and authority (e.g. the targeting of the Four Old Things during the Cultural Revolution in China, 1966-7); generation of publicity in order to provoke support, outrage, or other response (such as the Taliban’s ruination of the Bamiyan Buddhas, 2001); wanting to gain access to spoils (e.g. sacking of the City of Benin, 1897); and opportunistic and organised looting (including thefts from the Iraq National Museum, 2003). During war, there is often also considerable collateral, inadvertent, and neglectful damage caused by armed forces.

Irregular warfare actors and terrorist organisations are often equally destructive of cultural heritage. Islamic terrorist attacks on the West, for example, are primarily focused on ‘soft targets’ that will attract considerable media attention and are deemed justifiable – if only to the perpetrators and facilitators – on the basis of being stages of decadence, degeneracy, and impurity. The result is, a terrorist attack profile that includes music concerts, nightclubs, sporting events, economic hubs, and magazine offices. These often go unrecognised as heritage, officially, and in popular consciousness, but they are, individually and collectively, emblematic of Western liberal democracies.

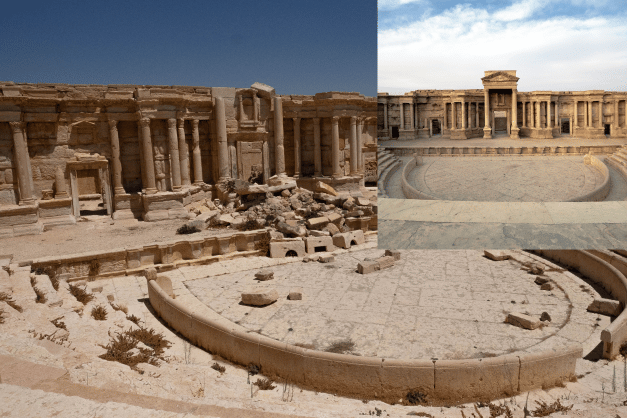

Cultural heritage is also used as a stage to amplify propaganda. During its hold on the World Heritage Site of Palmyra, for instance, Daesh routinely used the ancient architecture publicly to execute prisoners and otherwise terrorise locals. With time being a dimension of power, the site was mobilised to intimidate and as a symbol of their (self-perception of) legitimacy.

Military forces are also increasingly involved in the humanitarian response to natural disasters around the world. As climate change takes its toll – through rising sea-level, heatwaves, and wildfires, as well as in driving displacement and conflict – the need to protect heritage will escalate.

Protecting heritage can, thereby, play a prominent role in safeguarding human security and the return to ‘normality’ in the aftermath of conflict. Heritage can help people find home again

Understanding the character of the heritage and conflict relationship better equips states to deliver peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction missions, mitigate threats, generate soft power advantage, as well as protect cultural heritage directly.

Heritage is a human rights issue, insofar as it relates to freedom of expression, thought, conscience, and religion. Protecting heritage can, thereby, play a prominent role in safeguarding human security and the return to ‘normality’ in the aftermath of conflict. Heritage can help people find home again.

Western military forces are increasingly conscious of these issues and are acting to build relevant capabilities. Examples include the US Army’s Civil Affairs and Psychological Operations Command’s 38G/6V Heritage and Preservation Officer Program and the British Army’s Cultural Property Protection Unit. These modern day ‘monuments men and women’ not only protect heritage in conflict theatres, but support operational readiness through related planning, training, and intelligence work.

This familiarity between soldiering and heritage is long-standing, and derives, in part, from the shared features of mapping, fieldwork, and the large-scale deployment of people and equipment. T.E. Lawrence (‘Lawrence of Arabia’) was an archaeologist before he was a soldier, and Augustus Pitt-Rivers, whose founding collection was the genesis of the Pitt Rivers Museum, made the opposite transition.

An escalation in heritage targeting and weaponisation [is intended] to either reinforce or erode people’s identities in and around conflict zones. Destruction in such contexts is often a matter of domination

Reflecting changes in modern warfare – from conventional wars of attrition and exhaustion to hybrid and subthreshold hostilities – state and non-state actors continue to deploy or destroy cultural heritage for political ends. Indeed, the current trajectory indicates an escalation in heritage targeting and weaponisation as part of strategies to either reinforce or erode people’s identities in and around conflict zones. Destruction in such contexts is often a matter of domination, and protection of resistance.

The Russian invasion is a case in point. President Putin has made clear that he believes Ukraine is an inalienable part of Russian history and culture. Despite these assertions, the targeting of Ukrainian cultural sites indicates an internal recognition of the robust and distinct character of Ukrainian identity. As the destruction goes on, however, the cultural affinity that remains between Russia and Ukraine is under threat as both become increasingly defined in opposition to one another. The Orthodox Church in Ukraine, for example, became autocephalous in 2019, meaning it split from the Moscow Patriarchate Church.

President Putin has made clear that he believes Ukraine is an inalienable part of Russian history and culture….[but] the targeting of Ukrainian cultural sites indicates an internal recognition of the robust and distinct character of Ukrainian identity

The display of burnt-out Russian armoured vehicles in cities across Ukraine, including Kyiv and Lviv, adds a modern twist to the conflict and heritage nexus. This material debris of combat is being transported from the battlefield and effectively converted into heritage for public consumption in almost real time. Together with viral memes on social media, most recognisably perhaps of Ukrainian farmers towing Russian tanks with their tractors, this heritage embodies an emotional truth for Ukrainians.

This physical and digital debris resonates with, and further informs, cultural narratives of independence and warrior ancestry. Ukrainians at once immortalise and are immortalised by Volodymyr the Great, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, Taras Shevchenko, and the Zaporizhian Cossacks riding horseback with sabres blazing through Gogol’s legends of Taras Bulba.

Cultural heritage cannot be separated from people – it is people. When we protect one, we protect the other.

Read here about current attempts to save Ukrainian heritage from Russian attack. On Hearing and Not Hearing Air-Raid Sirens is about Dr Olena Styazhkina, a Ukranian historian and writer, currently working to save historical documents in her homeland. Her story, translated by Oxford languages expert, Professor Polly Jones, can be read here

These topics are explored further in Cultural Heritage in Modern Conflict: Past, Propaganda, Parade (Tim Clack and Mark Dunkley editors) published by Routledge.

Dr Timothy Clack is the Chingiz Gutseriev Fellow at the School of Anthropology & Museum Ethnography (SAME) and School of Archaeology. He is also a Senior Research Fellow of Oxford’s Changing Character of War Centre. He Tweets as @AnthroClack